A hip fracture is a partial or complete break in the upper section of the femur, which forms the hip joint. Elderly people are more likely to sustain a hip injury thanks to poorer mobility and weaker bones, and the repercussions can be life-changing.

Hip fractures and hip injuries can lead to a variety of different complications — most notably, difficulty in walking and maintaining mobility. But different kinds of hip fractures can present in different ways and may need various rehabilitation exercises and plans.

There are three main types of hip fractures to be aware of, and they can have different ramifications for the person involved. Here’s our guide to different types of hip fractures and what they mean.

Jump straight to…

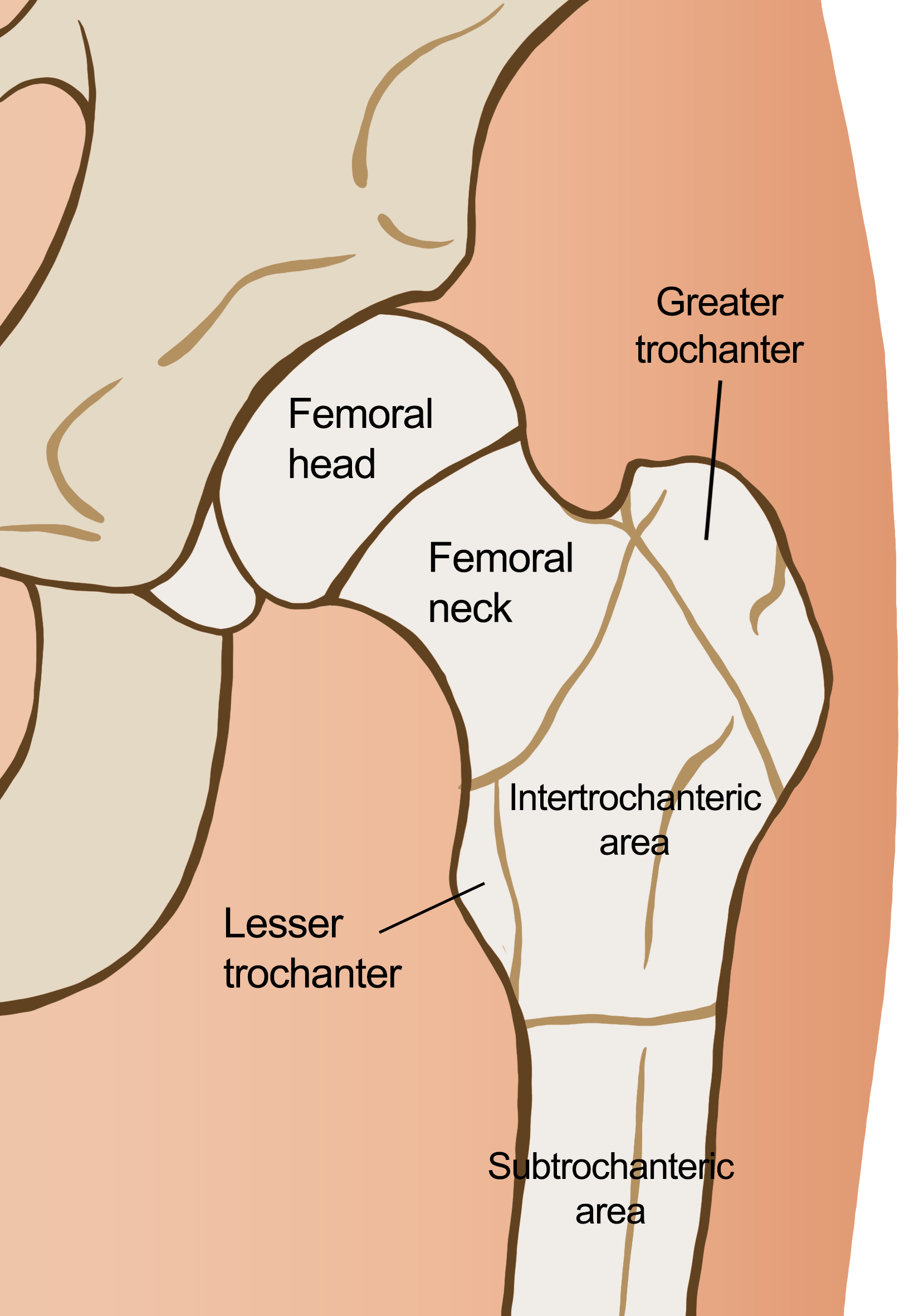

The anatomy of the hip joint

Just like any other joint in the body, the hip is incredibly important to our range of movement in day-to-day life. The hip itself is the point of contact between your trunk and your legs, and any hip injury can severely impact your overall mobility.

The hip is referred to as a ‘ball and socket’ joint. It is exactly how it sounds — the head of the femur is ball-shaped and slots into the hip socket of the pelvis. Using medical terminology, the femoral head (top of the femur) fits into the acetabulum (hip socket).

The hip joint is separated into three key areas that can all be fractured.

Whilst the hip joint is formed from two separate bones, the hip is split into different areas. These are:

| 1. Intracapsular Area | Femoral head | The ‘ball’ part of the joint that slots into the hip socket. |

| Femoral neck | The hourglass-shaped section below the femoral head. | |

| 2. Intertrochanteric Area | The area of bone below the femoral neck and before the long part of the femur. It contains the greater and lesser trochanters. | |

| 3. Subtrochanteric Area | The top of the shaft of the femur. | |

Whilst the anatomy of the hip is relatively straightforward, fractures in the joint can cause an array of issues and complications to the individual. The most important thing we can do is try and prevent hip fractures from occurring in the first place, and protect the hip at all costs.

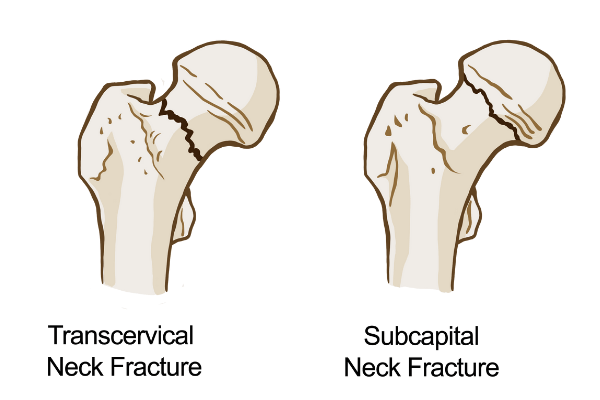

Intracapsular Fractures

As the intracapsular area includes both the femoral head and neck, fractures in this area can occur in either (or both) of these sections. Femoral neck fractures tend to be more common as this section is more exposed to impact than the femoral head (femoral head fractures only make up about 1% of hip fractures).

Femoral neck fractures are common for people who have osteoporosis.

Femoral neck fractures are usually just an inch or two below the hip joint itself. These, along with intertrochanteric hip fractures, account for around 90% of all hip fractures. Any fracture in the intracapsular area can easily be caused by osteoporosis and lesser bone density in older people.

Hip fractures in the femoral neck can cause further complications depending on the severity. The main risk is that the fracture interrupts or prevents the bloody supply to the ball and socket of the hip joint.

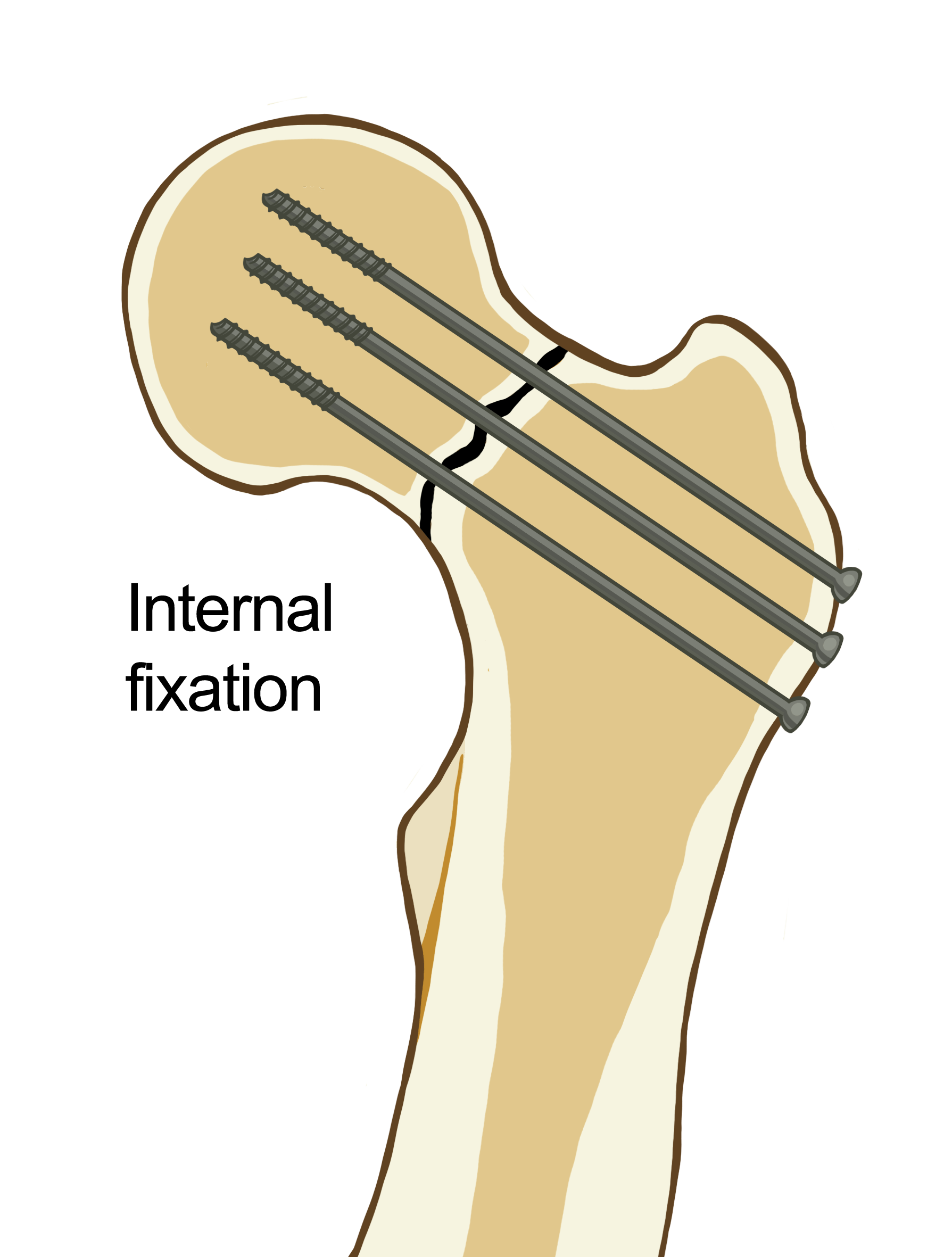

Treating Intracapsular Fractures

The treatment for any hip fracture will depend on whether the fracture is displaced. If a fracture is displaced, it means that the bone has come out of alignment at some point. Any displaced fracture will need to be re-aligned first.

If an intracapsular fracture is nondisplaced (has no alignment issues), then the most common treatment is to pin the bone back in place with the femoral head in the correct position whilst it heals. This will also help to prevent the femoral head from slipping or becoming dislodged, which could result in a hip replacement.

Screws to secure the femoral head back to the femur will help to fix a femoral neck fracture.

Displaced femoral neck fractures can be a bit more complicated due to the disrupted blood flow. Doctors will need to assess how much blood supply has been lost, which could mean a weakened femoral head and an increased chance of arthritis. Displaced fractures often requirement a hip replacement to avoid any further complications.

Some intracapsular fractures may not require surgery to heal, but the individual will need to ensure that they are not putting any weight on the leg/hip affected and might have to use crutches for many weeks.

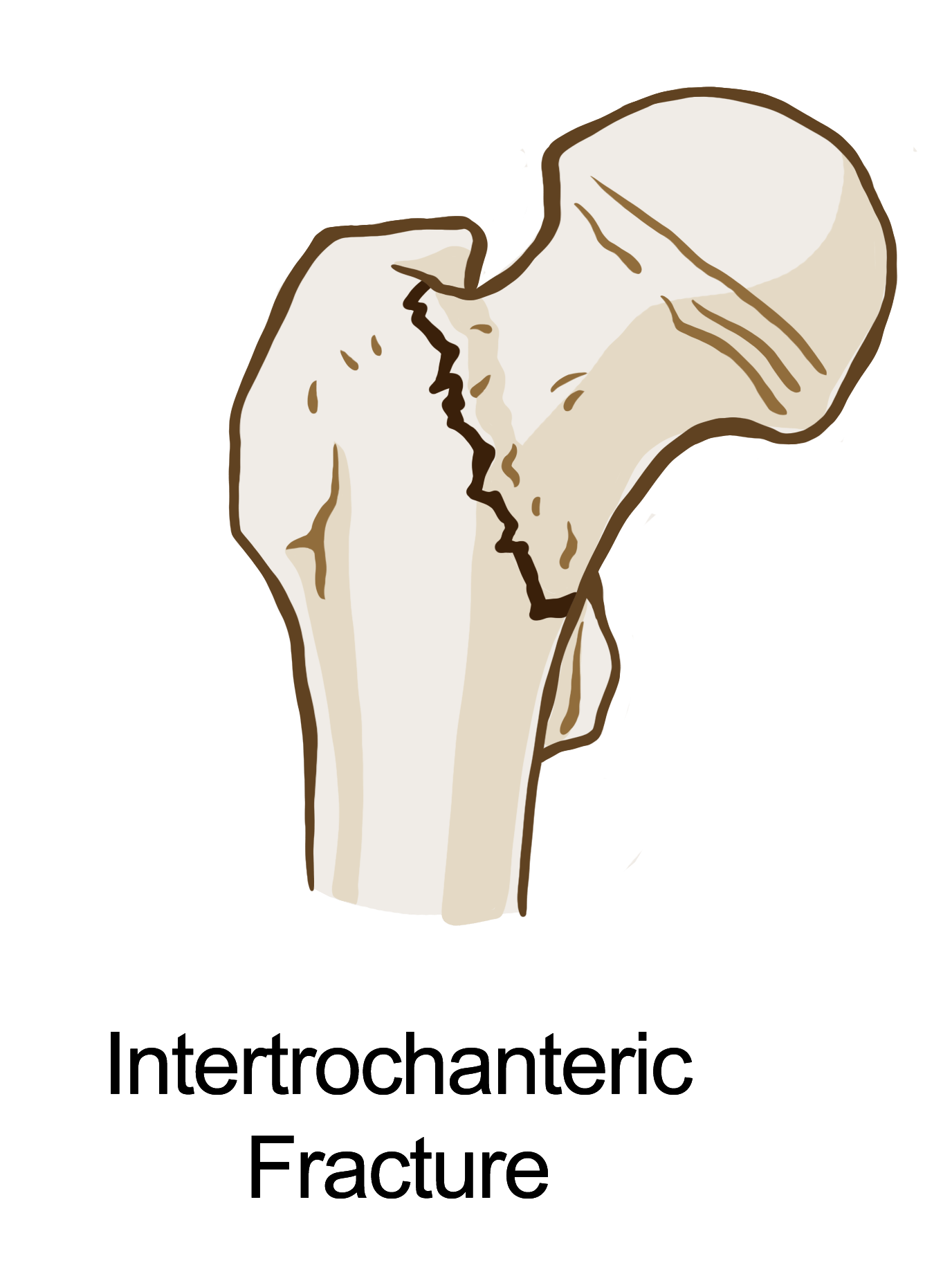

Intertrochanteric Fractures

Slightly further down from the intracapsular area, intertrochanteric fractures are about three or four inches below the hip joint in the thickest section of bone. You can actually feel your greater trochanter — it is the bony protrusion on the side of your hip.

Intertrochanteric fractures can run along the thickest part of the bone from the lesser trochanter to the greater trochanter.

Intertrochanteric fractures can sometimes also be compound fractures and may contain multiple bone fragments. The bone may break right across from the lesser trochanter to the greater trochanter. It may also cause other breakages along this fault line.

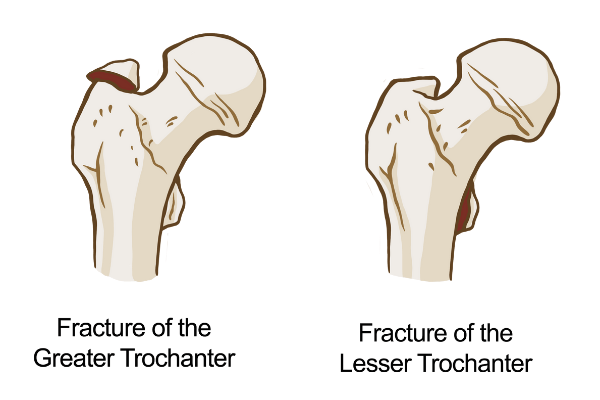

Fractures in the Lesser and Greater Trochanters can also happen, although these tend to be much smaller.

Hip fractures in this area tend to be less complex because they do not affect the blood flow.

Treating Intertrochanteric Fractures

Hip fractures in the intertrochanteric area are often treated with surgery, pinning the bones back into place. Again, it will depend on whether the fracture is displaced or not.

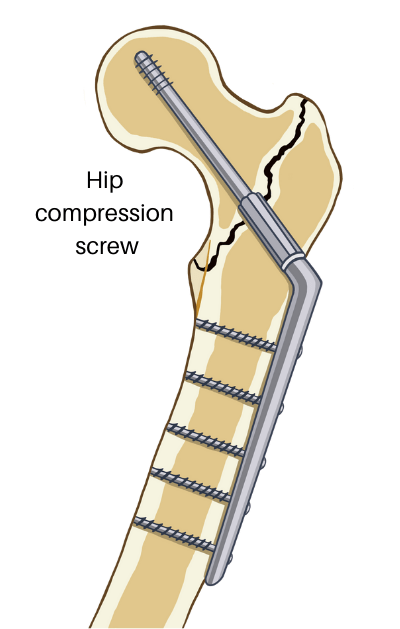

Surgeons can take a couple of approaches with these fractures, and both approaches will require a screw or nail being attached along the femur to anchor other screws in place. This structure will then hold the femur together and in place and reinforce the alignment of the femoral head in the hip joint.

Intertrochanteric fractures are often fixed in place using multiple screws.

Any smaller fractures in the area, i.e., along the top of the greater trochanter, can often be treated without surgery.

Subtrochanteric Fractures

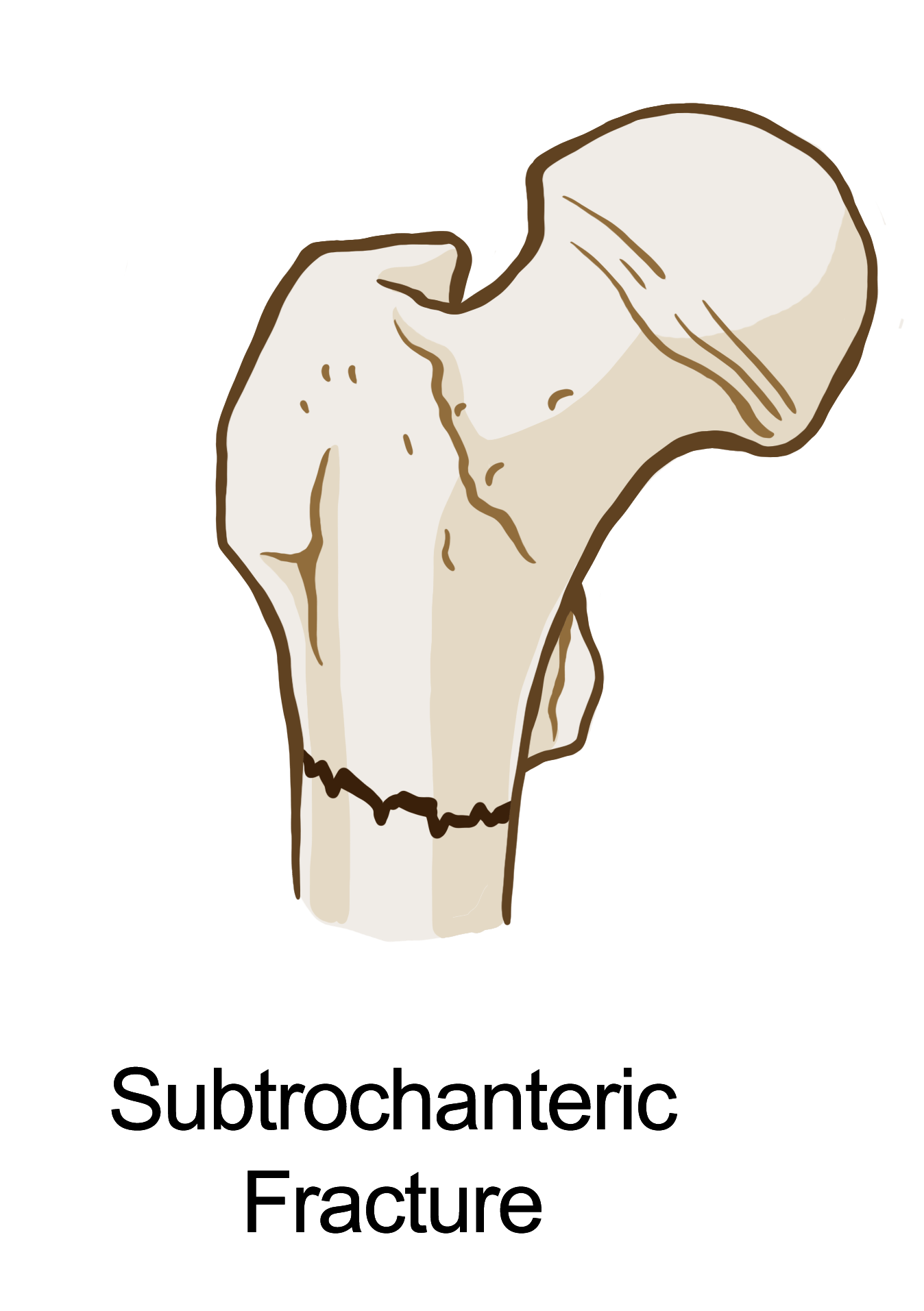

Hip fractures in the subtrochanteric area are somewhat less common than the other two areas we have looked at. That being said, they can still happen.

Subtrochanteric fractures occur further down the femur and are sort of borderline leg fractures. As the femur is such a long bone — running right from your hip socket to the top of your knee — there’s a lot of length where fractures can occur. The subtrochanteric area is just high enough to be classed as part of the hip joint.

Subtrochanteric fractures are further down the leg, but still class as a type of hip fracture.

Subtrochanteric can vary between a straight, clean break and a compound fracture. Surgeons will only be able to tell the severity of the fracture with an X-ray or MRI scan.

Treating Subtrochanteric Fractures

Just like the other fractures, doctors will need to assess whether the fracture is displaced before taking a course of action. One risk that is associated with subtrochanteric fractures is the possibility of bone rotation; the femur may appear to be aligned but could easily be twisted or displaced due to rotation.

Similar to intertrochanteric fractures, a longer screw will need to be placed along the length of the femur to secure the bone in place. This is often one long nail attached to a screw through the femoral head.

Alternatively, to prevent the bone from rotating whilst healing, surgeons may use a side plate along the outside of the femur with multiple screws securing the bone in place laterally.

Summary

Hip fractures can be caused by a few different things, so it’s always important to try and prevent them from happening in the first place. If you ever suspect that someone has sustained a hip fracture, then it’s important to seek medical attention.

Whilst hip fractures can vary in location and severity, the treatment remains consistent for all of them; limited weight-bearing and surgery if necessary. The key focus for any treatment of a hip fracture will be to repair the joint and ensure that it can remain as functional as possible.